Traduzione generata automaticamente

Mostra originale

Mostra traduzione

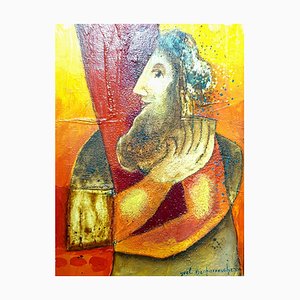

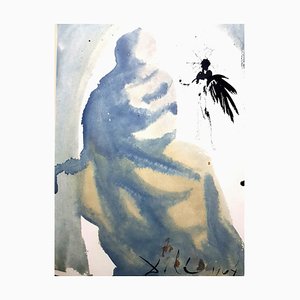

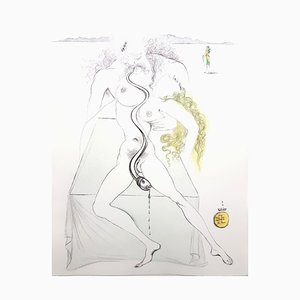

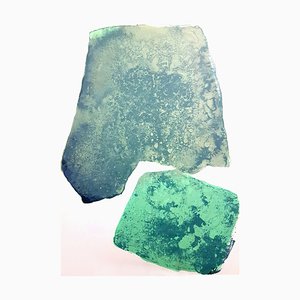

Sonia Delaunay - Original Watercolor on paper Dimensions: 21 x 21 cm. Authentified by her son Charles Delaunay on the back. Sonia Delaunay was known for her vivid use of color and her bold, abstract patterns, breaking down traditional distinctions between the fine and applied arts as an artist, designer and printmaker. Born Sarah Stern on November 14, 1885 in Gradizhsk, Ukraine, she was adopted in 1890 by her maternal uncle, Henri Terk, a lawyer in St. Petersburg, where she grew up, exposed to music and art, and learning several foreign languages. In 1903, she moved to Germany to study drawing with Ludwig Schmidt-Reutler (1863–1909) at the Karlsruhe academy of fine arts; Arnold Schoenberg (1874–1951), composer-to-be, was among her classmates there. In 1905, she traveled to Paris where she attended art classes at the Académie de la Palette, learned printmaking from Rudolf Grossman (1889–1941), and met Amédée Ozenfant (1886–1966), André Dunoyer de Segonzac (1884–1974), and Jean-Louis Boussingault (1883–1943). Sonia spent much of her time at exhibitions and galleries in Paris, which showed works by Paul Cézanne, Vincent Van Gogh, Pierre Bonnard, and Edouard Vuillard, as well as Les Fauves, Henri Matisse and André Derain. She did, however, maintain contact with Germany, exhibiting at the Galerie Der Sturm, Berlin, in 1913, 1920 and 1921. During her first year in Paris, Sonia met the German collector and art-dealer, Wilhelm Uhde (1874–1947), whom she married on December 5, 1908, and whose Montparnasse gallery, the Galerie Notre-Dame des Champs, showed her first solo exhibition. Through Uhde, Sonia encountered many painters, including Pablo Picasso, Georges Braque, Maurice de Vlaminck, and Robert Delaunay (1885–1941). In 1910, Sonia divorced Uhde by mutual agreement, married Delaunay that same year, and gave birth to their son, Charles, in January 1911. Together Sonia and Robert Delaunay pursued the study of color, influenced by theories of Michel-Eugène Chevreul (1786–1889). Sonia’s interest in simultaneous contrast, as evidenced in her early collages, book bindings, small painted boxes, cushions, waistcoats and lampshades, led to one of her first large-scale works, the painting of the Bal Bullier (1912–1913), a popular Parisian dance-hall. Sonia’s first “simultaneous dresses,” a mix of squares and triangles of taffeta, tulle, flannelette, moiré, and corded silk, date from this period. Friendship with the poet Blaise Cendrars (1887–1961) resulted in Sonia’s colored-squares fabric binding for his poem Pâques à New York (1912), and her collaboration on an accordion-type book of Cendrars’ long 207 verse poem, La Prose du Transsibérien et de la Petite Jehanne de France (1913), whose unique format, a vertical scroll almost two meters long, is said to have been inspired by the Delaunays’ fascination with the Eiffel Tower. Other aspects of modern urban life that inspired Sonia’s work included electric street lights (Prismes électriques, 1914) and publicity, though the various studies that she did for projects for Chocolat, Zenith, and Le Rêve gas stoves all remained unrealized. When World War I was declared in 1914, Sonia Delaunay was in the Basque border town of Fuenterrabía with her husband, and they did not return to Paris until 1920. During this period, they traveled to Madrid and to the village of Vila do Condo in Portugal, and Valença da Minho, where she painted still-lifes and market scenes. While in Madrid, she had become interested in Flamenco singers, and continued to do versions of this subject in Portugal (Flamenco Singer, 1916). Sonia Delaunay claimed that living in the Iberian Peninsula had opened her eyes to the very origin of light. Settled in Madrid, she started to engage in interior decoration (Casa Sonia) in addition to designing clothes and costumes. In 1918, Serge Diaghilev (1872–1929) commissioned her to do the costumes for a Ballets Russes production of Cléopatre, which opened in London. The soprano Aga Lahovska persuaded Delaunay to design the costumes for a production of the opera Aida at the Liceo in Barcelona. Following the Aida, she was invited to decorate a new nightclub, the Petit Casino, scheduled to open in a remodeled theatre in Madrid. She virtually gave up painting between 1918 and 1935 when she lost the financial support of her relatives in St. Petersburg with the outbreak of the Russian Revolution in 1917. When Sonia and Robert Delaunay returned to Paris in 1920, they took an apartment at 19 boulevard Malesherbes, which Sonia completely redecorated with furniture that she designed herself—most pieces now in the Musée des Arts Décoratifs in Paris. The Delaunay home was open to members of Dada and Surrealist groups: Tristan Tzara (1896–1963), Philippe Soupault (1897–1990), André Breton (1896–1982), Louis Aragon (1897–1982), René Crevel (1900–1935), etc. Delaunay’s friendship with Tzara lasted more than forty years: they launched the famous ‘poem-dresses’ (words and colors in ever new relationships through body movement), and in July 1923 Delaunay designed the costumes for Tzara’s play, Coeur à gaz, which was produced as part of an evening of experimental theatre, with music by Georges Auric (1899–1983), and Crevel in one of the parts. Delaunay’s involvement in fabrics began as early as 1923 with the more than fifty designs that she provided a silk manufacturer in Lyon. In 1924, she founded her own company with four directors, among them the prominent couturier and furrier, Jacques Heim (1899–1967). Her greatest success came in 1925, at the Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes, for which she designed and decorated her Boutique Simultanée, run with the help of Heim. Sonia Delaunay was extraordinarily prolific up to the 1930 world Depression; her work became known in London at Liberty’s and in department stores in New York, not to mention her profitable collaboration with the Amsterdam department store of Metz & Co., begun in 1925. She was designing not only fabrics and fashion, but carpets and panels and handbags, and also costumes for two films: Vertige, directed by Marcel L’Herbier (1888–1979), and Le p’tit Parigot by René Le Somptier (both 1926). Her renown for her fabrics and clothing brought her an invitation to speak at the Sorbonne, January 27, 1927, on “The Influence of Painting on the Art of Clothing,” where she introduced the revolutionary idea of prêt-à-porter (ready-to-wear). During the 1930s, Sonia Delaunay’s life was divided between fashion design, articles in magazines, interior decorating, and projects for window displays and posters. In 1937, the Exposition Internationale des Arts et Techniques dans la Vie Moderne, backed by Léon Blum’s (1872–1950) Popular Front government, solicited the participation of the Delaunays in the decoration of two temporary exhibition buildings: the Pavillon des Chemins de Fer and the Palais de l’Air. Voyages lointains and Portugal, which Sonia painted for the railroad pavilion, were awarded a gold medal. The Delaunays were ardent promoters of abstract art: they became members of the Abstraction-Création group in 1931 and organized the first Salon des Réalités Nouvelles in 1939. After her husband’s death in 1941, Sonia continued her energetic support of abstract art, while reestablishing Robert’s reputation with a number of exhibitions of his work and bequests of his work and hers to public institutions. By the 1950s, Delaunay was beginning to exhibit her own work again, particularly in the gallery in Auteuil of Colette Allendy. In 1953 the Galerie Bing mounted a solo show, which brought her renewed attention, and she was also represented in exhibitions in Paris (Musée National d’Art Moderne and Galerie Suzanne Michel) and Rome. In 1955 the Rose Fried Gallery in New York gave her her first solo show in the United States. The following year she had exhibitions in Grenoble, Havana, Venice, Rome and Milan. In 1958 the Städtisches Kunsthaus in Bielefeld organized a large exhibition of her works, comprising some 260 pieces, and thereafter she participated regularly in exhibitions devoted to the work of the Moderns. In 1964 Delaunay became the first living female artist to have a retrospective exhibition at the Louvre, thanks to her donation of 117 works by herself and Robert (Donation Delaunay). In March 1965 she sent a gouache and an oil to Salon des femmes peintres, a show exclusive to women painters. And in July 1965 she began collaboration with Jacques Damase (b. 1931) on a book of poems and pochoirs, using documents in her possession from Robert’s collection of poems by his friends. It appeared under the title Rhythmes-Couleurs, with a preface by Michel Hoog. One of the first important exhibitions of Delaunay’s work, which took place in Paris in 1965 after her meeting Damase, was called ‘L’Expo 1925,’ at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs, where an entire room was devoted to her fabric designs and dresses. In 1967, with Damase’s help, she enjoyed what may have been her greatest tribute, a full-scale retrospective of her work, consisting of almost two hundred pieces, at the Musée National d’Art Moderne. By the time Sonia Delaunay died at home in Paris on December 5, 1979, she had received the Légion d’honneur and painted the poster for the International Women’s Year of UNESCO (both 1975), collaborated in costume designs for a production at the Comédie-Française (Luigi Pirandello’s Six Characters in Search of an Author, 1978), and taken part in the Paris-Moscow Exhibition at the Centre Pompidou (1979), to which she had donated her entire graphic work in 1976. Her recognition as an artist was such that President Georges Pompidou (1911–1974), on an official visit to the United States, brought one of Sonia Delaunay’s paintings as a gift from the French governmen

Sonia Delaunay - Acquerello originale su carta Dimensioni: 21 x 21 cm. Autenticato da suo figlio Charles Delaunay sul retro. Sonia Delaunay era nota per il suo vivido uso del colore e per i suoi audaci modelli astratti, abbattendo le distinzioni tradizionali tra le belle arti e le arti applicate come artista, designer e stampatore. Nata Sarah Stern il 14 novembre 1885 a Gradizhsk, in Ucraina, fu adottata nel 1890 dallo zio materno, Henri Terk, un avvocato di San Pietroburgo, dove crebbe, esponendosi alla musica e all'arte e imparando diverse lingue straniere. Nel 1903, si trasferì in Germania per studiare disegno con Ludwig Schmidt-Reutler (1863-1909) all'Accademia di Belle Arti di Karlsruhe; Arnold Schoenberg (1874-1951), futuro compositore, era tra i suoi compagni di classe. Nel 1905, si recò a Parigi dove frequentò le lezioni d'arte all'Académie de la Palette, imparò la stampa da Rudolf Grossman (1889-1941) e incontrò Amédée Ozenfant (1886-1966), André Dunoyer de Segonzac (1884-1974) e Jean-Louis Boussingault (1883-1943). Sonia trascorse molto del suo tempo alle mostre e alle gallerie di Parigi, che mostravano opere di Paul Cézanne, Vincent Van Gogh, Pierre Bonnard e Edouard Vuillard, così come Les Fauves, Henri Matisse e André Derain. Tuttavia, ha mantenuto il contatto con la Germania, esponendo alla Galerie Der Sturm di Berlino nel 1913, 1920 e 1921. Durante il suo primo anno a Parigi, Sonia incontrò il collezionista e mercante d'arte tedesco Wilhelm Uhde (1874-1947), che sposò il 5 dicembre 1908, e la cui galleria di Montparnasse, la Galerie Notre-Dame des Champs, mostrò la sua prima mostra personale. Attraverso Uhde, Sonia incontrò molti pittori, tra cui Pablo Picasso, Georges Braque, Maurice de Vlaminck e Robert Delaunay (1885-1941). Nel 1910, Sonia divorziò da Uhde di comune accordo, sposò Delaunay lo stesso anno e diede alla luce il loro figlio, Charles, nel gennaio 1911. Insieme Sonia e Robert Delaunay perseguirono lo studio del colore, influenzati dalle teorie di Michel-Eugène Chevreul (1786-1889). L'interesse di Sonia per il contrasto simultaneo, come evidenziato nei suoi primi collage, rilegature di libri, piccole scatole dipinte, cuscini, panciotti e paralumi, portò a una delle sue prime opere su larga scala, il dipinto del Bal Bullier (1912-1913), una popolare sala da ballo parigina. I primi "abiti simultanei" di Sonia, un mix di quadrati e triangoli di taffetà, tulle, flanella, moiré e seta cordata, risalgono a questo periodo. L'amicizia con il poeta Blaise Cendrars (1887-1961) portò Sonia a realizzare la rilegatura in tessuto a quadretti colorati per il suo poema Pâques à New York (1912), e la sua collaborazione su un libro a fisarmonica del lungo poema in 207 versi di Cendrars, La Prose du Transsibérien et de la Petite Jehanne de France (1913), il cui formato unico, un rotolo verticale lungo quasi due metri, si dice sia stato ispirato dal fascino della Torre Eiffel dei Delaunay. Altri aspetti della vita urbana moderna che ispirarono il lavoro di Sonia furono i lampioni elettrici (Prismes électriques, 1914) e la pubblicità, anche se i vari studi che fece per i progetti di Chocolat, Zenith e le stufe a gas Le Rêve rimasero tutti irrealizzati. Quando la prima guerra mondiale fu dichiarata nel 1914, Sonia Delaunay era nella città basca di confine di Fuenterrabía con suo marito, e non tornarono a Parigi fino al 1920. Durante questo periodo, viaggiarono a Madrid e al villaggio di Vila do Condo in Portogallo, e Valença da Minho, dove dipinse nature morte e scene di mercato. Mentre era a Madrid, si era interessata ai cantanti di flamenco, e continuò a fare versioni di questo soggetto in Portogallo (Flamenco Singer, 1916). Sonia Delaunay sosteneva che vivere nella penisola iberica le aveva aperto gli occhi sull'origine stessa della luce. Stabilitasi a Madrid, iniziò a dedicarsi alla decorazione d'interni (Casa Sonia) oltre a disegnare abiti e costumi. Nel 1918, Serge Diaghilev (1872-1929) le commissionò i costumi per una produzione dei Ballets Russes di Cléopatre, che aprì a Londra. Il soprano Aga Lahovska convinse Delaunay a disegnare i costumi per una produzione dell'opera Aida al Liceo di Barcellona. Dopo l'Aida, fu invitata a decorare un nuovo locale notturno, il Petit Casino, la cui apertura era prevista in un teatro ristrutturato a Madrid. Ha praticamente abbandonato la pittura tra il 1918 e il 1935 quando ha perso il sostegno finanziario dei suoi parenti a San Pietroburgo con lo scoppio della rivoluzione russa nel 1917. Quando Sonia e Robert Delaunay tornarono a Parigi nel 1920, presero un appartamento al 19 boulevard Malesherbes, che Sonia ridecorò completamente con mobili da lei stessa disegnati, la maggior parte dei quali si trova ora al Musée des Arts Décoratifs di Parigi. La casa dei Delaunay era aperta ai membri dei gruppi dadaisti e surrealisti: Tristan Tzara (1896-1963), Philippe Soupault (1897-1990), André Breton (1896-1982), Louis Aragon (1897-1982), René Crevel (1900-1935), ecc. L'amicizia di Delaunay con Tzara durò più di quarant'anni: lanciarono i famosi 'abiti-poesia' (parole e colori in rapporti sempre nuovi attraverso il movimento del corpo), e nel luglio 1923 Delaunay disegnò i costumi per la commedia di Tzara, Coeur à gaz, che fu prodotta come parte di una serata di teatro sperimentale, con musica di Georges Auric (1899-1983), e Crevel in una delle parti. Il coinvolgimento di Delaunay nei tessuti iniziò già nel 1923 con gli oltre cinquanta disegni che fornì a un produttore di seta di Lione. Nel 1924, fondò la propria azienda con quattro direttori, tra cui il famoso couturier e pellicciaio Jacques Heim (1899-1967). Il suo più grande successo arrivò nel 1925, all'Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes, per la quale progettò e decorò la sua Boutique Simultanée, gestita con l'aiuto di Heim. Sonia Delaunay fu straordinariamente prolifica fino alla depressione mondiale del 1930; il suo lavoro divenne noto a Londra da Liberty e nei grandi magazzini di New York, per non parlare della sua proficua collaborazione con i grandi magazzini di Amsterdam Metz & Co. iniziata nel 1925. Disegnava non solo tessuti e moda, ma tappeti e pannelli e borse, e anche costumi per due film: Vertige, diretto da Marcel L'Herbier (1888-1979), e Le p'tit Parigot di René Le Somptier (entrambi del 1926). La sua fama per i suoi tessuti e i suoi abiti le procurò un invito a parlare alla Sorbona, il 27 gennaio 1927, su "L'influenza della pittura sull'arte dell'abbigliamento", dove introdusse l'idea rivoluzionaria del prêt-à-porter (ready-to-wear). Durante gli anni '30, la vita di Sonia Delaunay si divide tra design di moda, articoli su riviste, decorazione di interni e progetti per vetrine e manifesti. Nel 1937, l'Exposition Internationale des Arts et Techniques dans la Vie Moderne, sostenuta dal governo del Fronte Popolare di Léon Blum (1872-1950), sollecitò la partecipazione dei Delaunay alla decorazione di due edifici espositivi temporanei: il Pavillon des Chemins de Fer e il Palais de l'Air. Voyages lointains e Portugal, che Sonia dipinse per il padiglione ferroviario, furono premiati con una medaglia d'oro. I Delaunay furono ardenti promotori dell'arte astratta: divennero membri del gruppo Abstraction-Création nel 1931 e organizzarono il primo Salon des Réalités Nouvelles nel 1939. Dopo la morte del marito nel 1941, Sonia continuò il suo energico sostegno all'arte astratta, mentre ristabiliva la reputazione di Robert con una serie di mostre del suo lavoro e lasciti di opere sue e di lei a istituzioni pubbliche. Negli anni Cinquanta, Delaunay cominciò a esporre di nuovo le proprie opere, in particolare nella galleria di Auteuil di Colette Allendy. Nel 1953 la Galerie Bing allestì una mostra personale che le portò nuova attenzione, e fu anche rappresentata in mostre a Parigi (Musée National d'Art Moderne e Galerie Suzanne Michel) e Roma. Nel 1955 la Rose Fried Gallery di New York le offre la sua prima personale negli Stati Uniti. L'anno seguente ha esposto a Grenoble, L'Avana, Venezia, Roma e Milano. Nel 1958 la Städtisches Kunsthaus di Bielefeld organizza una grande mostra delle sue opere, composta da circa 260 pezzi, e in seguito partecipa regolarmente alle mostre dedicate al lavoro dei Moderni. Nel 1964 Delaunay diventa la prima artista donna vivente ad avere una retrospettiva al Louvre, grazie alla sua donazione di 117 opere sue e di Robert (Donazione Delaunay). Nel marzo 1965 invia una gouache e un olio al Salon des femmes peintres, una mostra riservata alle pittrici. E nel luglio 1965 inizia la collaborazione con Jacques Damase (nato nel 1931) per un libro di poesie e pochoirs, utilizzando i documenti in suo possesso della collezione di poesie di Robert dei suoi amici. Apparve con il titolo Rhythmes-Couleurs, con una prefazione di Michel Hoog. Una delle prime mostre importanti del lavoro di Delaunay, che ebbe luogo a Parigi nel 1965 dopo il suo incontro con Damase, fu chiamata "L'Expo 1925", al Musée des Arts Décoratifs, dove un'intera sala era dedicata ai suoi disegni di tessuti e abiti. Nel 1967, con l'aiuto di Damase, ha goduto di quello che forse è stato il suo più grande tributo, una retrospettiva completa del suo lavoro, composta da quasi duecento pezzi, al Musée National d'Art Moderne. Quando Sonia Delaunay morì nella sua casa di Parigi il 5 dicembre 1979, aveva ricevuto la Légion d'honneur e dipinto il poster per l'Anno Internazionale della Donna dell'UNESCO (entrambi nel 1975), collaborato ai disegni dei costumi per uno spettacolo alla Comédie-Française (Sei personaggi in cerca d'autore di Luigi Pirandello, 1978) e partecipato all'Esposizione Parigi-Mosca al Centre Pompidou (1979), alla quale aveva donato tutta la sua opera grafica nel 1976. Il suo riconoscimento come artista fu tale che il presidente Georges Pompidou (1911-1974), in visita ufficiale negli Stati Uniti, portò uno dei quadri di Sonia Delaunay come regalo del governo francese

Contattaci

Fai un'offerta

Abbiamo notato che sei nuovo su Pamono!

Accetta i Termini e condizioni e l'Informativa sulla privacy

Contattaci

Fai un'offerta

Ci siamo quasi!

Per seguire la conversazione sulla piattaforma, si prega di completare la registrazione. Per procedere con la tua offerta sulla piattaforma, ti preghiamo di completare la registrazione.Successo

Grazie per la vostra richiesta, qualcuno del nostro team vi contatterà a breve.

Se sei un professionista del design, fai domanda qui per i vantaggi del Programma Commerciale di Pamono