Traduzione generata automaticamente

Mostra originale

Mostra traduzione

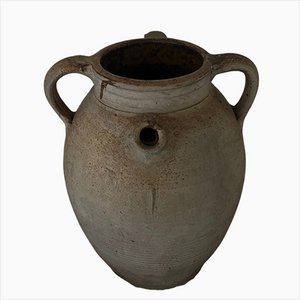

Schneider mouth blown crystal candleholders with biomorphic form. A truy unique set, in almost perfect condition given their age. A rare piece of history.

Matching table lamp sold seperately.

The Schneider Glassworks (Verreries Schneider), established by brothers Charles and Ernest Schneider in Epinay-sur-Seine, France, in 1917, was among the leading producers of fine-art glass between the two world wars, creating exuberantly colorful vessels and lighting fixtures in both the Art Nouveau and Art Deco styles. The factory’s highpoint was the 1920s, when it created iconic chandeliers and exquisitely decorated cameo glass vases that are still in high demand today.

Born in the last quarter of the 19th century in Château-Thierry, near Paris, Charles and Ernest Schneider moved with their family at a young age to Nancy, a major center of Art Nouveau design, particularly known for glass. Among the city’s master makers was the crystal studio Daum, where both brothers worked at the turn of the 20th century, Ernest in sales, and Charles receiving training in the engraving and decoration workshop, while concurrently learning drawing and modeling with Henri Bergé and attending the École des Beaux-Arts in Nancy. In 1904, he enrolled at the École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts, in Paris, where he studied painting and metal engraving and regularly showed in the engraving section of the Salon de la Société des Artistes Français, twice receiving a prize.

Around 1912 the brothers and their friend, architect Henri Wolf, bought a small glass factory specializing in lightbulbs, renaming it Schneider Frères et Wolff. The partners enticed a group of about 20 workers from the Daum workshop to join the company, which produced high-quality cameo vases and lamps until the outbreak of World War I, in 1914, when Charles, Ernest and most of the workers were called up to fight. The Schneiders were demobbed in 1917 and reopened the factory, initially making practical glassware for hospitals. After the war, to fund their reentry into the art-glass market, they sold shares in the company, now named the Société Anonyme des Verreries Schneider. The success of the elegant drinking glasses and Art Nouveau-style cameo vases they produced allowed the brothers to buy back the shares, at which point they renamed the factory Verreries Schneider.

When a fire destroyed the Gallé studios in 1918, the Schneiders offered space to a group of the company’s artists so they could continue production. In return, they taught Charles marqueterie de verre. Similar to wood marquetry, this process involves cutting sections out of a glass surface and filling them with pieces of a contrasting color. In 1921, Schneider trademarked his technique for making cameo glass lamps and vases — exemplified in this piece from the early 1920s — which he signed “Le Verre Français” or “Charder,” the latter perhaps a portmanteau combining his first and last names. These works were popular and sold well at France’s top department stores, including Galeries Lafayette and Le Bon Marché. More elaborate, one-of-a-kind pieces from the studio were signed “Schneider” and offered at Paris art galleries like Au Vase Etrusque and Delvaux.

The Schneiders participated in the 1925 Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Moderne in Paris, at which Charles was a member of the jury. The company was at its peak, expanding both its design repertoire and the number of workers, to 500. During this period, it began moving away from the organic shapes of Art Nouveau to the more geometric designs of Art Deco, with some pieces embodying a kind of transitional style, such as this chandelier. Charles also began experimenting with pigmented powders, fine crushed glass mixed with metal oxides, which yielded brilliant, iridescent colors when applied to a glass surface.

A large portion of the factory’s art glass production was sold in the United States. When the U.S. stock market crashed in 1929, demand was all but obliterated, and the company struggled to stay afloat throughout the 1930s. Ernest died in 1937, and during World War II, the factory was seized by German troops and used as a canteen. In 1950, Charles and his son set up a new factory called Cristalleries Schneider in Epinay-sur-Seine, which for several years produced free-blown glass vases, small sculptures and lighting fixtures to some acclaim. Charles Schneider died in 1952, and the factory eventually closed in 1981.

Portacandele in cristallo soffiato a bocca Schneider dalla forma biomorfa. Un set davvero unico, in condizioni quasi perfette data l'età. Un raro pezzo di storia.

Lampada da tavolo abbinata venduta separatamente.

La vetreria Schneider (Verreries Schneider), fondata dai fratelli Charles ed Ernest Schneider a Epinay-sur-Seine, in Francia, nel 1917, è stata tra i principali produttori di vetro artistico tra le due guerre mondiali, creando vasi e apparecchi di illuminazione dai colori esuberanti sia in stile Art Nouveau che Art Déco. L'apice della produzione è stato raggiunto negli anni Venti, quando la fabbrica ha creato lampadari iconici e vasi in vetro cammeo squisitamente decorati che sono ancora oggi molto richiesti.

Nati nell'ultimo quarto del XIX secolo a Château-Thierry, vicino a Parigi, Charles ed Ernest Schneider si trasferirono con la famiglia in giovane età a Nancy, un importante centro di design Art Nouveau, particolarmente noto per il vetro. Tra i maestri della città c'era lo studio di cristalli Daum, dove entrambi i fratelli lavorarono all'inizio del XX secolo: Ernest nelle vendite e Charles nel laboratorio di incisione e decorazione, mentre contemporaneamente imparava a disegnare e modellare con Henri Bergé e frequentava l'École des Beaux-Arts di Nancy. Nel 1904 si iscrive all'École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts di Parigi, dove studia pittura e incisione su metallo ed espone regolarmente nella sezione incisione del Salon de la Société des Artistes Français, ricevendo due volte un premio.

Intorno al 1912 i fratelli e il loro amico, l'architetto Henri Wolf, acquistano una piccola fabbrica di vetro specializzata in lampadine, ribattezzandola Schneider Frères et Wolff. I soci convincono un gruppo di circa 20 operai provenienti dall'officina Daum a unirsi all'azienda, che produce vasi e lampade a cammeo di alta qualità fino allo scoppio della Prima Guerra Mondiale, nel 1914, quando Charles, Ernest e la maggior parte degli operai vengono chiamati a combattere. Nel 1917 gli Schneider vennero congedati e riaprirono la fabbrica, inizialmente producendo pratici oggetti in vetro per gli ospedali. Dopo la guerra, per finanziare il loro rientro nel mercato del vetro artistico, vendettero le azioni della società, ora denominata Société Anonyme des Verreries Schneider. Il successo degli eleganti bicchieri e dei vasi a cammeo in stile Art Nouveau prodotti permise ai fratelli di riacquistare le azioni, e a quel punto ribattezzarono la fabbrica Verreries Schneider.

Quando nel 1918 un incendio distrusse gli studi Gallé, gli Schneider offrirono uno spazio a un gruppo di artisti dell'azienda per continuare la produzione. In cambio, insegnarono a Charles la marqueterie de verre. Simile all'intarsio del legno, questo processo consiste nel tagliare sezioni di una superficie di vetro e riempirle con pezzi di colore contrastante. Nel 1921, Schneider registrò la sua tecnica per realizzare lampade e vasi in vetro cammeo - esemplificati in questo pezzo dei primi anni Venti - che firmò "Le Verre Français" o "Charder", quest'ultimo forse un portmanteau che combinava il suo nome e cognome. Queste opere erano popolari e si vendevano bene nei grandi magazzini francesi, tra cui le Galeries Lafayette e Le Bon Marché. I pezzi più elaborati e unici dello studio erano firmati "Schneider" e offerti alle gallerie d'arte parigine come Au Vase Etrusque e Delvaux.

Gli Schneider parteciparono all'Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Moderne di Parigi del 1925, alla quale Charles fu membro della giuria. L'azienda era al suo apice, con un'espansione sia del repertorio di design che del numero di dipendenti, fino a raggiungere le 500 unità. In questo periodo, l'azienda inizia ad abbandonare le forme organiche dell'Art Nouveau per passare ai disegni più geometrici dell'Art Déco, con alcuni pezzi che incarnano una sorta di stile di transizione, come questo lampadario. Charles iniziò anche a sperimentare le polveri pigmentate, vetro finemente frantumato mescolato con ossidi metallici, che davano colori brillanti e iridescenti quando venivano applicati su una superficie di vetro.

Gran parte della produzione di vetro artistico della fabbrica veniva venduta negli Stati Uniti. Quando il mercato azionario statunitense crollò nel 1929, la domanda fu quasi azzerata e l'azienda lottò per rimanere a galla per tutti gli anni Trenta. Ernest morì nel 1937 e, durante la Seconda Guerra Mondiale, la fabbrica fu sequestrata dalle truppe tedesche e utilizzata come mensa. Nel 1950, Charles e suo figlio fondarono una nuova fabbrica, le Cristalleries Schneider, a Epinay-sur-Seine, che per diversi anni produsse vasi di vetro soffiato a bocca libera, piccole sculture e apparecchi di illuminazione, riscuotendo un certo successo. Charles Schneider morì nel 1952 e la fabbrica chiuse nel 1981.

Contattaci

Fai un'offerta

Abbiamo notato che sei nuovo su Pamono!

Accetta i Termini e condizioni e l'Informativa sulla privacy

Contattaci

Fai un'offerta

Ci siamo quasi!

Per seguire la conversazione sulla piattaforma, si prega di completare la registrazione. Per procedere con la tua offerta sulla piattaforma, ti preghiamo di completare la registrazione.Successo

Grazie per la vostra richiesta, qualcuno del nostro team vi contatterà a breve.

Se sei un professionista del design, fai domanda qui per i vantaggi del Programma Commerciale di Pamono