Traduzione generata automaticamente

Mostra originale

Mostra traduzione

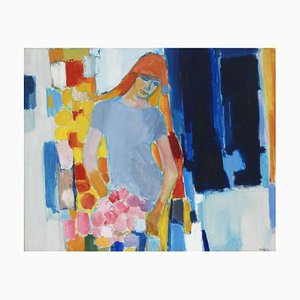

Miss Ethel Mortlock an oil on canvas called 'Town' of Marie Adelaide Brassey (aged 3) who became Marchioness of Willingdon (see below) and is buried in the Nave at Westminster Abbey, signed and dated 1878. Picture 60 x 45 cm

Ethel Mortlock (1865-1928) an extraordinary woman and sought after portrait painter. Born in Cambridge and lived in London. She exhibited at The Royal Academy between years 1878-1893 no less than 29 paintings also at the Grosvenor Galleries. Many of Paintings in museums (See History below and her sitters).

Marie Adelaide Brassey - Marie Adelaide Freeman-Thomas, Marchioness of Willingdon, GBE, CI DStJ (née Brassey; 24 March 1875 – 30 January 1960) was a daughter of Thomas Brassey, 1st Earl Brassey. On 20 July 1892, she married Freeman Thomas , 1st Marquess of Willingdon (12 September 1866 – 12 August 1941), the future Governor General of Canada and Viceroy of India. She became : Invested as an Imperial Order of the Crown of India (C.I.) in 1917, Decorated with the Kaisar-i-Hind Gold Medal , Invested as a Dame of Justice, Venerable Order of St John (D.J.St. J.),Decorated with the Order of Mercy. Invested as a Dame Commander of the Order of the British Empire (DBE) in December 1917. Invested as a Dame Grand Cross of the Order of the British Empire (GBE) in the 1924 Birthday Honours. Marie Canyon on the Cowichan River, Vancouver Island is named for her, commemorating a 1930 canoe trip from Cowichan Lake down that river to the city of Duncan, British Columbia. The Lady Willingdon Hospitol in Lahore, Pakistan is named after her .The Lady Willingdon Hospital in Manali, Himachal Pradesh, India, is named after her.

About Ethel Mortlock : Her clientèle of sitters included members of the aristocracy and European nobility and included, by her account, the Shah of Persia (1900) and the ‘Chinese Ambassador’, Li Hung Chang (who was actually the Chinese Viceroy), à propos which sitting the Sketch published an illustrated interview with Ethel in August 1896. Ethel was thought pretty grand by the American papers who reported that Chang had to go to her studio for sittings in 1896 rather than she wait upon him. He brought her a roll of silk and a white jade palette as presents. Li Hung Chang was a pretty big cheese; his wife had two thousand servants waiting on her. The Chatham, NY, Courier reported that Ethel had painted every Ambassador who had come to London. These last clients, allegedly by failing to pay the £1000 charged for their portraits, landed Ethel in trouble. They were, of course, conveniently unavailable to the bankruptcy commissioners so this sob-story could not be checked. Strapped for cash she was caught out when the executors of a racehorse owner called Edward Overall Bleakley found, in his effects, IOUs for hundreds of pounds (Bleakley had bequeathed his own portrait by Ethel to Manchester Infirmary [Daily News, 1.8.98]). Ethel went to court, claiming that these were offset by painting commissions, but the court found against her and she was told to pay up. Now saddled with legal costs, she was caught again when Captain Noel Hoare, her man of business, died and it was found that he had mortgaged to Hoare’s Bank, without her knowledge (she said), three properties in Sloane Street that she had been building. She tried to buy back one of these but lost a £500 deposit when she could not complete, making a bad situation rather worse. Bleakley’s executors now broke her and her examination in bankruptcy in 1901 can be read in the PRO as above. Her troubles were attributed to extravagance and betting - the Bleakley IOUs were assumed to be in fact gambling debts and the creditors now included all sorts of tradesmen and the Hotel Cecil where Ethel was then living, presumably in some style. She did not help herself by claiming an income of £250 p.a. when individual commissions were on her own account at the £1000 mark as above, meaning that the Chinese and Persian portraits alone would have occupied her last eight years and she would have obtained these prestigious commissions at the age of 18 (she gave her age as 26). Faced by the raised eyebrows of her superiors in mental arithmetic Ethel then upped her declared usual income to a still rather modest £800. She claimed to keep no sort of cash book, accounts, or any memoranda. Proceedings closed with Ethel declared bankrupt and a number of people out of pocket; the settlement was at 7/6 in the pound. Ethel went back to her easel. Some financial aspects seem never to have been sorted out; funds in Chancery relating to her, Hoare and Bleakley were still being recorded in the London Gazette every few years at least up to 1938; maybe the born in Cambridge; she appears never to have married. The 1881 census had not heard of her - she may have been in the United States at that time. However, standard works about Victorian painters, such as the Antique Collectors’ Club Dictionary of British Artists (Johnson %26 Greutzner, 1976) and their Dictionary of Victorian Painters (C Wood, 2nd edition, 1978) tell us that she was a pupil of Sir William Orchardson (who came to London in 1863) and that by 1904 she had exhibited 29 works at the Royal Academy. I have listed these, usually prestigious, sitters, who included Don Carlos (Duke of Madrid), the Duchess of Wellington and the Earl of Ashburnham, as a footnote to this article. They cannot have been by any means her whole output; surely not all her clients would have agreed to being hung in public nor perhaps to spare the work they had paid for from their own and their families’ walls. There may also have been works submitted to the R.A. which did not appeal to the Hanging Committee, such as her 1885 portrait of Colonel Burnaby. But to get in year after year bespeaks considerable ability; she was clearly competent with her brush if not at accountancy.

Her portrait of the albino-complexioned Robert Lowe, 1st (and only) Viscount Sherbrooke, held by Nottingham Castle Museum, was executed in 1878 when Ethel was later said to have been only 16 - evidence of a remarkable talent if this were true, particularly as the painting was exhibited at the Royal Academy and in 1880 at the Walker gallery in Liverpool [see the Liverpool Mercury, 5.10.1880]. Sherbrooke himself left the painting to his wife and then to the Council of the University of London but there was some dispute over this legacy [Pall Mall Gazette, 6.10.92]. Not only did she achieve exhibition at the R.A., sometimes her work was singled out for comment by The Times. A monochrome portrait by Ethel of George Earl Church, a celebrated explorer of South America, (now held by Brown University in New England) and her portrait of Don Carlos were described in 1883 as ‘strong portraits’.In 1888 her portrayals of William C Endicott, the US Secretary for War and of Colonel Coxon were described as ‘good likenesses painted with much power’ and were exhibited following a ‘prolonged visit to the United States‘ [Glasgow Herald, 26.3.88]. Works not shown by the RA include an 1887 portrait of Mary Endicott (later Mrs Joseph Chamberlain) that can now be seen in the Glen Magna Farms mansion in Maine . The Church and Endicott works suggest that Ethel may have spent her American time seeking clients in New England. Her commissions also included a portrait of the Irish-American rancher John Adair (d.1885), which work is now in the Panhandle-Plains Museum in Canyon, Texas, and has a note on its back of her name and gives her address as 122 Sloane Street.

A portrait of the 2nd Duke of Wellington hangs in Gloversville public library NY, probably commissioned by his friend, the library’s founder Elder Levi Parsons. Also not recorded in the Royal Academy list, but mentioned in A Dictionary of Portrait Painters Up To 1920 is a portrait of the 2nd Duke of Wellington which is believed to be one of the earliest portraits of a sitter smoking a cigarette, which hangs in Stratfield Saye. Another exotic sitter had been the Sultan of Johore, who had visited England in 1891. As a 21st century price guide, her rather crestfallen ‘Lady Godiva’ was on offer on the internet for $20,000. She could paint horses, too.

The Royal Academy Exhibitors list allows Ethel’s addresses to be traced, at least in part. In 1878 she was in Thistle Grove, SW10 which runs off the Brompton Road towards Chelsea. By 1884 she was at 122, Sloane Street, where she was at home to the census taken seven years later. By 1900 she had moved into the Cecil Hotel off Sloane Square and, her hotel bill presumably unpaid, moved the next year to 46a, Pall Mall. In fact in December 1887 the Blackburn Standard reported that she was ‘not in America’ but in Sloane Street, ‘working hard .. for the 1888 Exhibition’.

Another portrait by Ethel was of Sir Walter Lowry Buller, the celebrated New Zealand ornithologist which is now in the NZ Museum in Wellington.The last work of hers that I have been able to discover (that of the Prince of Wales) seems to date to 1926.

Miss Ethel Mortlock un olio su tela intitolato "Città" di Marie Adelaide Brassey (3 anni) che divenne marchesa di Willingdon (vedi sotto) ed è sepolta nella navata dell'Abbazia di Westminster, firmato e datato 1878. Immagine 60 x 45 cm

Ethel Mortlock (1865-1928) è una donna straordinaria e una ricercata ritrattista. Nata a Cambridge e vissuta a Londra. Ha esposto alla Royal Academy tra gli anni 1878-1893 non meno di 29 dipinti, anche alla Grosvenor Galleries. Molti dei suoi dipinti sono conservati nei musei (si veda la storia qui di seguito e i suoi ritrattisti).

Marie Adelaide Brassey - Marie Adelaide Freeman-Thomas, Marchesa di Willingdon, GBE, CI DStJ (nata Brassey; 24 marzo 1875 - 30 gennaio 1960) era figlia di Thomas Brassey, I conte Brassey. Il 20 luglio 1892 sposò Freeman Thomas, 1° Marchese di Willingdon (12 settembre 1866 - 12 agosto 1941), futuro Governatore generale del Canada e Viceré dell'India. Divenne: Investita dell'Ordine Imperiale della Corona d'India (C.I.) nel 1917, decorata con la Medaglia d'Oro Kaisar-i-Hind, Investita della Dama di Giustizia, Venerabile Ordine di San Giovanni (D.J.St. J.), decorata con l'Ordine della Misericordia. Investita del titolo di Dama Comandante dell'Ordine dell'Impero Britannico (DBE) nel dicembre 1917. Investita della Gran Croce dell'Ordine dell'Impero Britannico (GBE) nel 1924. Il Marie Canyon sul fiume Cowichan, nell'isola di Vancouver, prende il nome da lei, in ricordo di un viaggio in canoa del 1930 dal Cowichan Lake lungo il fiume fino alla città di Duncan, nella Columbia Britannica. Il Lady Willingdon Hospitol di Lahore, in Pakistan, porta il suo nome. Il Lady Willingdon Hospital di Manali, nell'Himachal Pradesh, in India, porta il suo nome.

Su Ethel Mortlock: la sua clientela comprendeva membri dell'aristocrazia e della nobiltà europea e includeva, secondo il suo racconto, lo Scià di Persia (1900) e l'"ambasciatore cinese", Li Hung Chang (che in realtà era il viceré cinese), a proposito del quale lo Sketch pubblicò un'intervista illustrata con Ethel nell'agosto 1896. Ethel era ritenuta piuttosto grandiosa dai giornali americani, i quali riportarono che nel 1896 Chang dovette recarsi nel suo studio per le sedute, piuttosto che essere lei ad aspettare lui. Le portò in dono un rotolo di seta e una tavolozza di giada bianca. Li Hung Chang era un pezzo grosso; sua moglie aveva duemila domestici che la servivano. Il Chatham, NY, Courier riportò che Ethel aveva dipinto tutti gli ambasciatori che erano venuti a Londra. Questi ultimi clienti, a quanto pare, non avendo pagato le 1.000 sterline richieste per i loro ritratti, misero Ethel nei guai. Naturalmente non erano disponibili per i commissari fallimentari e quindi questa storia strappalacrime non poteva essere verificata. Quando gli esecutori testamentari di un proprietario di cavalli da corsa di nome Edward Overall Bleakley trovarono tra i suoi effetti personali cambiali per centinaia di sterline (Bleakley aveva lasciato in eredità il proprio ritratto di Ethel al Manchester Infirmary [Daily News, 1.8.98]), Ethel fu colta in flagrante. Ethel si rivolse al tribunale, sostenendo che queste somme erano compensate dalle commissioni per i dipinti, ma il tribunale le diede torto e le fu intimato di pagare. Ora che deve sostenere le spese legali, viene nuovamente incastrata quando il capitano Noel Hoare, il suo uomo d'affari, muore e si scopre che aveva ipotecato alla Hoare's Bank, a sua insaputa, tre proprietà in Sloane Street che lei stava costruendo. Lei cercò di riacquistare uno di questi, ma perse un deposito di 500 sterline quando non riuscì a portarlo a termine, peggiorando una situazione già difficile. Gli esecutori testamentari di Bleakley la fecero fallire e il suo esame per bancarotta nel 1901 può essere letto nel PRO come sopra. I suoi problemi vennero attribuiti alla stravaganza e alle scommesse: si ipotizzò che le cambiali di Bleakley fossero in realtà debiti di gioco e i creditori includevano ora ogni sorta di commercianti e l'Hotel Cecil, dove Ethel viveva, presumibilmente con un certo stile. Non si è aiutata dichiarando un reddito di 250 sterline l'anno, quando le commissioni individuali erano per suo conto pari a 1.000 sterline come sopra, il che significa che i ritratti cinesi e persiani da soli avrebbero occupato i suoi ultimi otto anni e che lei avrebbe ottenuto queste prestigiose commissioni all'età di 18 anni (ha dichiarato la sua età di 26 anni). Di fronte alle sopracciglia alzate dei suoi superiori in aritmetica mentale, Ethel alzò quindi il suo reddito abituale dichiarato a 800 sterline, ancora piuttosto modesto. Dichiarava di non tenere alcun tipo di libro cassa, di contabilità o di memorandum. Il procedimento si concluse con la dichiarazione di bancarotta di Ethel e l'esborso di un certo numero di persone; l'accordo fu di 7/6 per sterlina. Ethel tornò al suo cavalletto. Alcuni aspetti finanziari sembrano non essere mai stati risolti; i fondi in Chancery relativi a lei, Hoare e Bleakley venivano ancora registrati nella London Gazette ogni pochi anni almeno fino al 1938; forse i nati a Cambridge; sembra che non si sia mai sposata. Nel censimento del 1881 non si hanno notizie di lei: forse in quel periodo si trovava negli Stati Uniti. Tuttavia, le opere standard sui pittori vittoriani, come l'Antique Collectors' Club Dictionary of British Artists (Johnson %26 Greutzner, 1976) e il loro Dictionary of Victorian Painters (C Wood, seconda edizione, 1978) ci dicono che fu un'allieva di Sir William Orchardson (che arrivò a Londra nel 1863) e che nel 1904 aveva esposto 29 opere alla Royal Academy. Ho elencato questi, solitamente prestigiosi, committenti, tra cui Don Carlos (Duca di Madrid), la Duchessa di Wellington e il Conte di Ashburnham, in una nota a piè di pagina di questo articolo. Non possono essere la totalità della sua produzione; sicuramente non tutti i suoi clienti avrebbero accettato di essere appesi in pubblico né forse di risparmiare le opere che avevano pagato per le loro pareti e quelle delle loro famiglie. È anche possibile che siano state presentate alla R.A. opere che non sono piaciute alla Commissione per l'Appendimento, come il ritratto del colonnello Burnaby del 1885. Ma il fatto di essere stata ammessa anno dopo anno denota una notevole abilità; era chiaramente competente con il pennello, se non con la contabilità.

Il suo ritratto dell'albino-complessato Robert Lowe, primo (e unico) visconte Sherbrooke, conservato dal Nottingham Castle Museum, fu eseguito nel 1878, quando Ethel avrebbe avuto solo 16 anni - prova di un talento notevole, se ciò fosse vero, soprattutto perché il dipinto fu esposto alla Royal Academy e nel 1880 alla Walker gallery di Liverpool [cfr. Liverpool Mercury, 5.10.1880]. Sherbrooke stesso lasciò il dipinto alla moglie e poi al Consiglio dell'Università di Londra, ma ci furono delle controversie su questo lascito [Pall Mall Gazette, 6.10.92]. L'artista non solo ottenne un'esposizione alla R.A., ma a volte le sue opere vennero commentate dal Times. Un ritratto monocromo di George Earl Church, un celebre esploratore del Sud America, (ora conservato dalla Brown University in New England) e il suo ritratto di Don Carlos furono descritti nel 1883 come "ritratti forti". Nel 1888 i suoi ritratti di William C Endicott, il segretario alla Guerra degli Stati Uniti, e del colonnello Coxon furono descritti come "buone sembianze dipinte con molta forza" e furono esposti dopo una "prolungata visita negli Stati Uniti" [Glasgow Herald, 26.3.88]. Tra le opere non esposte alla RA c'è un ritratto del 1887 di Mary Endicott (poi signora Joseph Chamberlain) che oggi si trova nella villa di Glen Magna Farms nel Maine. Le opere di Church e di Endicott suggeriscono che Ethel potrebbe aver trascorso il suo periodo americano alla ricerca di clienti nel New England. Tra le sue commissioni c'è anche il ritratto del ranchero irlandese-americano John Adair (morto nel 1885), che oggi si trova al Panhandle-Plains Museum di Canyon, in Texas, e sul cui retro è annotato il suo nome e il suo indirizzo: 122 Sloane Street.

Un ritratto del 2° Duca di Wellington è appeso nella biblioteca pubblica di Gloversville (NY), probabilmente commissionato dal suo amico, il fondatore della biblioteca, Elder Levi Parsons. Un altro ritratto del II Duca di Wellington, non registrato nell'elenco della Royal Academy ma menzionato in A Dictionary of Portrait Painters Up To 1920, che si ritiene sia uno dei primi ritratti di un seduto che fuma una sigaretta, è appeso a Stratfield Saye. Un altro ritratto esotico fu quello del Sultano di Johore, che visitò l'Inghilterra nel 1891. Come guida al prezzo del XXI secolo, la sua "Lady Godiva", alquanto contrariata, è stata offerta su Internet per 20.000 dollari. Sapeva dipingere anche i cavalli.

L'elenco degli espositori della Royal Academy consente di rintracciare, almeno in parte, gli indirizzi di Ethel. Nel 1878 si trovava a Thistle Grove, SW10, che si trova sulla Brompton Road in direzione di Chelsea. Nel 1884 si trovava al 122 di Sloane Street, dove era di casa nel censimento effettuato sette anni dopo. Nel 1900 si era trasferita al Cecil Hotel, vicino a Sloane Square, e l'anno successivo, non avendo presumibilmente pagato il conto dell'albergo, si trasferì al 46a di Pall Mall. In realtà, nel dicembre 1887 il Blackburn Standard riportava che lei non era "in America", ma a Sloane Street, "lavorando sodo... per l'Esposizione del 1888".

Un altro ritratto di Ethel fu quello di Sir Walter Lowry Buller, il celebre ornitologo neozelandese, che oggi si trova al NZ Museum di Wellington. L'ultima opera di Ethel che sono riuscito a scoprire (quella del Principe di Galles) sembra risalire al 1926.

Contattaci

Fai un'offerta

Abbiamo notato che sei nuovo su Pamono!

Accetta i Termini e condizioni e l'Informativa sulla privacy

Contattaci

Fai un'offerta

Ci siamo quasi!

Per seguire la conversazione sulla piattaforma, si prega di completare la registrazione. Per procedere con la tua offerta sulla piattaforma, ti preghiamo di completare la registrazione.Successo

Grazie per la vostra richiesta, qualcuno del nostro team vi contatterà a breve.

Se sei un professionista del design, fai domanda qui per i vantaggi del Programma Commerciale di Pamono